- Mediterranean Hope - Federazione delle chiese evangeliche in Italia

- mh@fcei.it

Harraga. Music that burns the border

Silvia Turati – MH operator in Lampedusa and Lebanon

Rome (NEV), 10 January 2018 – The “Lo sguardo dalle frontiere” (A Look from the Border) editorial is written by operators of Mediterranean Hope (MH) – the Refugee and Migrant Programme promoted by the Federation of Protestant Churches in Italy (FCEI). This week’s “look” comes from Lampedusa.

“Harrag, ça reste toujours dans ma mentalité… dans mon esprit, dans ma tête, bon courage inshallah les frères…”

“Harrag, this will always remain in my way of thinking…in my spirit, in my head, good luck brothers, God willing…”

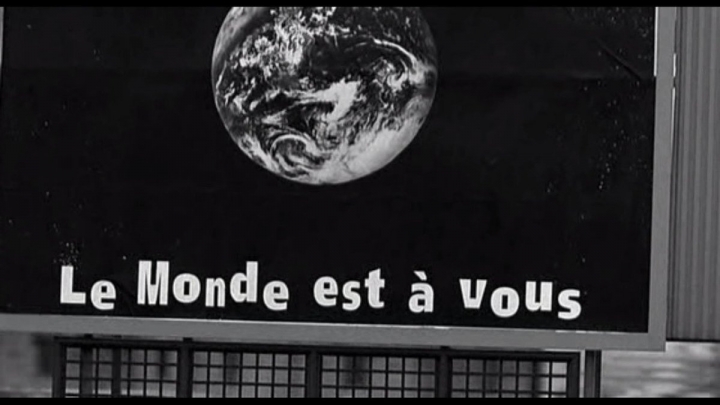

This is how the Tunisian song begins, a sort of anthem for the harraga: the young men who burn the border. Harraga is a word in Moroccan and Algerian dialect, which has its origin in the Arab word haraqa, meaning burn. This is how the young North Africans who cross the sea without documents define themselves: they burn the borders.

The Mediterranean is not crossed, but is burned: just like the souls of these young men. I have been seeing these faces on the streets of Lampedusa for a month now. With some of them, I have shared stories, memories and music.

Amìr shows me a YouTube video of different rap songs. We are having dinner, a group of Italian and Arab friends. Bashir starts singing and has a beautiful voice. A video with images of Paris plays. Words are rapped out, talking about a young man who chooses to leave, in a mixture of emotions ranging from the desire for redemption to the sense of guilt towards his mother, who he may never embrace again. But he repeats that he will leave, that his life is lost where he lives and that his country leaves him no other choice. He will leave as a loser or winner and, if he lives, he will find happiness elsewhere.

The authors of these songs are young men, who record, edit and then publish the videos on YouTube. The dreams of young Tunisians in Lampedusa have a rap melody, which they rap out and recite before each journey, during the crossing, and upon every arrival. The music and shouted words free them from fears and guilty feelings and give them courage.

Amìr shows me the video he shot during his first trip to Sicily: he is on a small boat, together with about twenty people. They are under the hot sun and are tired. It took forty hours to reach the Italian coast, that time. Amìr tells me that they voluntarily left in bad weather, so as to escape the controls of the Tunisian coastguard. The boat bounced amidst waves of up to four metres in height. “I have seen death in the face” he tells me. In the days after his arrival, those images would replay in his head as he lay down to sleep. “But I would do it again. One thousand, two thousand times, until death”.

I ask him why. Why does he and hundreds and thousands of other young people have this burning desire to leave, to live elsewhere?

On the one hand, there is undoubtedly the repression in his country, arbitrary revocation of freedom, widespread corruption in the various strata of society. On the other hand, there is the economic crisis and high unemployment, especially among the young. Amìr studied and worked as a pharmacist. His monthly salary barely allowed him to rent an apartment and buy something to eat every day. He studied for many years and yet he barely managed to cover his basic needs. Then comes summer and his village, a tourist destination a few kilometres from Sfax, is repopulated by Tunisians living in Europe, some in France, some in Belgium and some elsewhere. They all return to their homeland to spend their holidays and to visit family members. They return wealthy, although with great sacrifice, but at the end of the year they have a salary that allows them to go on holiday. When they return home, they are well dressed. Sometimes they buy a car. And send money to their mothers. They are the example of those who have made it, they are the ones who have won.

Amìr saw them every summer and one day he realised that he too, like so many others, felt anger. That day, he decided that he no longer wanted to live that life, a life of mere survival, without money and without the possibility of becoming someone. So, he left, one, two, three, four times, it doesn’t matter how many times he was forcibly repatriated. The danger of the sea will not stop him, nor the money paid to traffickers, nor the risk of being rejected or the harrowing wait in the hotspot before knowing his fate. Nor will he be stopped by the cold nights spent in the open to avoid being put on the wrong plane, the one that brings you back. Nothing will stop him.

Amìr and all the others left with the music of the harraqa in their ears and a fire in their heart. It is in the way they think, in their spirit and in their head. There are those who made it, and redeemed themselves. There are those who left and tried living in Europe, but could not do it, so they went back. And there are those who will never stop trying.